Introduction¶

In nuclear medicine, radiopharmaca are mostly used for diagnostic imaging (with SPECT or PET) and activity concentration measurements in samples (with a gamma counter). For that purpose, the radiopharmacon is labeled with a single photon or a positron emitting isotope. The photon energy of the single photon emitter is ideally between 100 and 200 keV, because that is a good compromise between good penetration of human tissues and good stopping by detector crystal. This is one of the reasons why 99mTc (emitting photons of 140 keV) is the most used radionuclide for single photon emission imaging. Positron emission will always produce 511 keV photons. That is a bit higher that we would have liked; for PET, there was no choice but to design detectors with sufficient stopping power. Ideally, the isotope would emit nothing else, because other emitted particles will not contribute to imaging, but they will damage the tissues (DNA) they traverse.

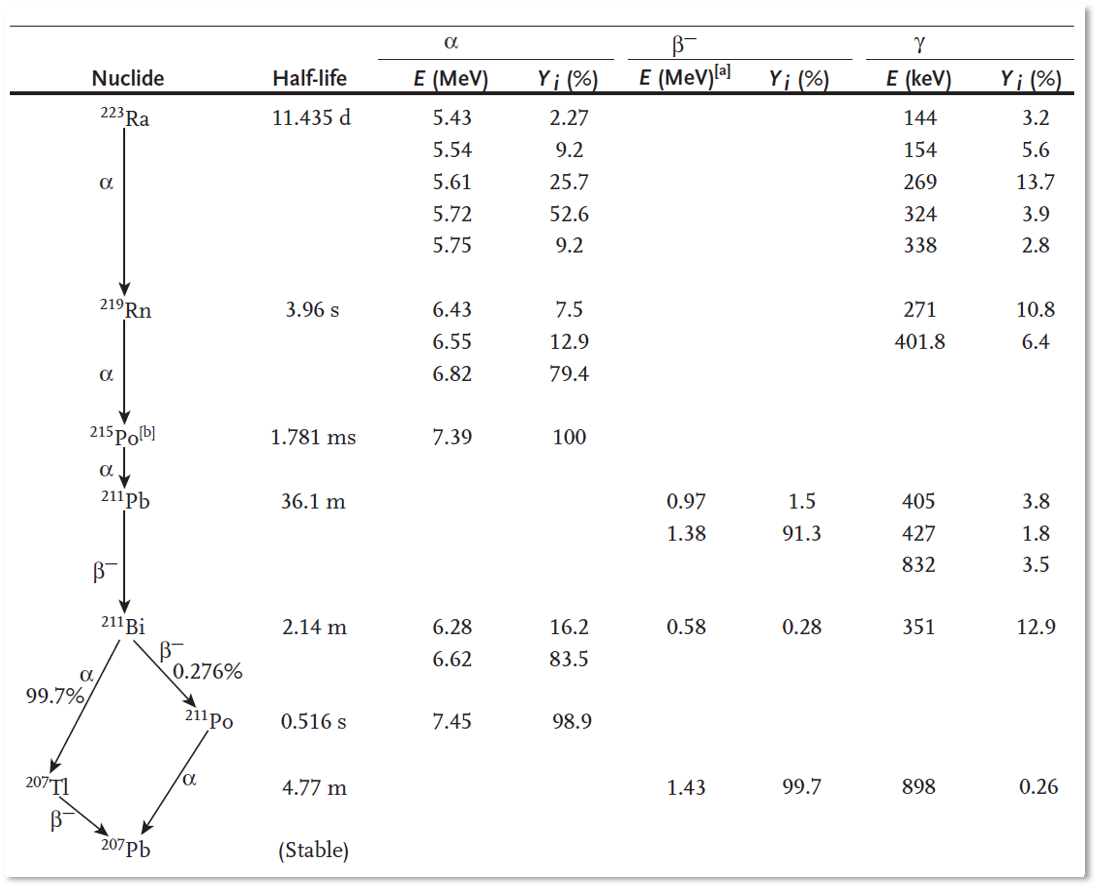

In recent years, radionuclide therapy is being used increasingly in cancer therapy. Radionuclide therapy makes use of molecules or other particles that accumulate preferentially in tumors, and which are labeled with radioactive isotopes (radionuclides). The aim is that this radiation will destroy the tumor, with minimal damage to the surrounding healthy tissues. For that purpose, the radiation should have a small penetration depth, as is the case for electrons (aka ), protons and α-particles (particle consisting of two protons and two neutrons, He2+). Table 1 and Figure 1 list the main emissions by a few of such radionuclides. The decay scheme of 223Ra is complex, because several of its daughter products are radiactive as well.

Most radionuclides used for therapy not only emit β or α particles, but also photons. The drawback of these photons is that they cause some radiation to the healthy tissues, but an advantage is that images can be made of the distribution of the radionuclide, enabling accurate dose verification (at least if the photon energies are suitable for imaging).

If the radiopharmacon has high affinity for the tumor and is very specific, i.e. it binds to the tumor and to (almost) nothing else, then the therapy can be more effective than external beam therapy for two reasons: it will treat all metastases, even small ones that may not be revealed by imaging, and a high radiation can be achieved with minimum damage to the surrounding healthy tissues.

To be effective, the amount of radioactivity administered to the patient should be high enough to destroy the tumors, but at the same time low enough to ensure that the radiation to healthy tissues (which may also accumulate some of the radioactivity) remains below safety limits. Consequently, it is important to estimate the expected dose distributions before treatment, and determine the delivered doses after treatment.

Table 1:Some radionuclides used in radionuclide therapy

131I | half-life | 8.03 days |

emission | mean energy (keV) | intensity |

182 | 100 | |

80 | 2.62 | |

284 | 6.12 | |

γ | 364 | 81.5 |

637 | 7.16 | |

723 | 1.77 |

Figure 1:Decay scheme of 223Ra, based on James E. Martin (2006).

MIRD formalism¶

MIRD refers to the Committee on Medical Internal Radiation Dose of the Society of Nuclear Medicine, which provides standard methods for internal radiation dosimetry. The focus has mostly been on producing reasonable dose estimates, to assess and control the risk associated with diagnostic imaging. These days, refinements are being made for more accurate dose calculations as required for radionuclide therapy.

The basic principles of internal dosimetry have already been explained in chapter Biological effects of radiation. MIRD uses the same principles, but formulates them slightly differently, introducing the dose rate and the S-factors. Another difference is that in chapter Biological effects of radiation, we integrated the activity over time to compute the total number of decays, and then computed the resulting dose from them. MIRD computes the dose associated with a single decay event (the dose rate), and integrates that over time.

The body of the patient is considered as a collection of 3D regions which contain an amount of radioactivity. To compute the dose (in Gy) received by a particular region, that region is treated as the target region , while all regions (including ) are considered one by one as source regions . The source region contains a time dependent activity , which is usually assumed uniform for convenience. At each point in time, that activity in the source region produces a dose rate in the target region. It is assumed that the two are proportional:

The activity is expressed in Bq, the dose rate in Gy/s. Consequently, the unit of is Gy / (Bq s) = Gy.

The factor , usually called the S-value, accounts for the following:

the probability that a particular particle (, ...) is produced during a decay in source region ,

the energy of each particle,

the probability that the particle reaches target region ,

the probability that it deposits (part of) its energy in ,

the mass of .

Because patients breathe, the shape of and and the distance between them may change, which would affect . Consequently, is a function of time, although that is typically ignored to keep the problem tractable. The S-value can be written as

is the mass of , which might be time dependent. The summation is over all emissions that may occur during a decay; is the branching ratio, i.e. the probability that emission will occur during a decay. is the energy of particle and gives the fraction of the energy that this particle is expected to deposit in . Thus, ϕ depends on the geometry and attenuation of and and the structures between and around them.

Since the dose rate in depends on all the radioactivity inside the patient’s body, we have to sum over all :

The dose in is obtained by integrating over time:

is some interesting time duration. In many cases, one can set , because the effective half life (combining decay half life and the biogical dynamics) of the radionuclide will be short. is the time integrated activity. To put in front of the integral sign, we had to make the common approximation that it does not depend on time.

The time integrated activity has no units, since Bq is the number of desintegrations per s, and a number is unitless. In practice, one often normalizes with the administered activity :

and therefore . The unit of is time, and for that reason it was called the residence time. If all the administered activity would stay for a short duration in the region and then vanish, then the same would be obtained. Since 2009, is called the time-integrated activity coefficient of [1]

To apply equation (5) for treatment planning or verification, we need

a 3D segmentation (delineation) of all important structures: organs, parts of organs, tumors, lesions, …, to produce the set of regions

the function for all possible region pairs (, ), all relevant particles and all relevant energies .

the activity as a function of time in all these regions,

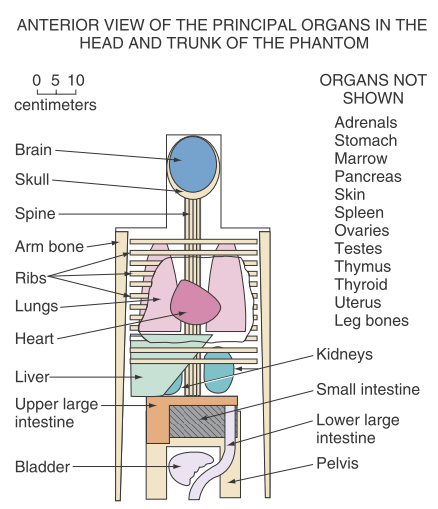

This should really be done for each individual patient (“personalized dosimetry”). Because that is very difficult, the segmentation and calculation of have first been addressed based on models of “average patients”. Figure 2 shows two such models, an early one based on simplified shapes and a more recent and realistic model using non-uniform rotational B-splines (NURBS). Similar models have been developed for children of different ages.

Figure 2:Left: representation of the average man for MIRD dose computation, as used in 1969 . Right: human body models based on non-uniform rational B-splines (NURBS).

When the patient model is available, the S-value can be computed with equation (2) for every region pair and for all radionuclides of interest. For electrons, positrons and α-particles, one can usually assume that their energy is deposited locally. That makes the calculation of very easy:

if , then

for :

On the other hand, for photons the calculations are very complicated and have to be done with Monte Carlo simulation.

Finally, to obtain a dose for a particular case, we need to determine the time-activity curves for each organ . Currently, this is done by acquiring SPECT or PET scans and manually segmenting the organs in the activity images, or in the corresponding CT images (relying on the spatial alignment produced by the SPECT/CT or PET/CT system). The time-activity curve is typically obtained by acquiring a dynamic SPECT or PET scan. For tracers with long (physical and biological) half life, some additional scans at later time points may be required. A good balance must be found between minimizing the number of scans (and their duration) for optimal patient comfort, and obtaining sufficient samples to reach an acceptable accuracy. In single photon emission imaging, some of the SPECT or SPECT/CT scans may be replaced by planar imaging to improve the temporal resolution (early after injection) or to reduce the imaging time (late after injection).

The anatomical models have been designed for assessing the typical radiation dose associated with diagnostic procedures. Because these doses are relatively low, it is assumed that the dose estimates obtained for such average patients are sufficiently accurate for producing clinical guidelines on the activity to be injected for different tracers and imaging tasks. Novel tracers are often first characterized in animal experiments. If those tests produce good results, they are evaluated in a small group of healthy volunteers, using one or multiple SPECT/CT or PET/CT scans, manual organ delineation and the S-values from the average patient. Because organ delineation is extremely time consuming, the delineation is usually restricted to source organs that accumulate a significant amount of activity and target organs that are known to be radiosensitive. The resulting radiation doses (in mGy or Gy) can then be converted to an effective dose (in mSv or Sv) by multiplying the energies with the appropriate quality factor Q (Table 1) and computing the weighted sum of the organ doses Table 2.

Application of such models to compute the required activity for radionuclide therapy is controversial, because the model may deviate strongly from the individual patient. However, because no clinical tools are currently available for accurate personalized dosimetry, they are often used for estimating tumor and organ doses in radionuclide therapy as well. This is likely to change in the next several years. It is found that “deep learning” (using multiple layers of convolutional neural networks or CNNs) is an excellent tool to capture the prior knowledge of experts, and it is increasingly being used for organ segmentation in clinical images. In addition, the execution time of Monte Carlo simulation can be decreased from several days to several minutes by implementing them in a clever way on GPU. Consequently, personalized dosimetry for radionuclide therapy in clinically acceptable times and with acceptable efforts seems possible.

Radiation Biologically Effective Dose (BED)¶

As mentioned above, for diagnostic applications, the effect of the radiation is converted to an effective dose in mSv using a simple weighted sum of organ doses. That approach is too simplistic for application in radionuclide therapy, where the doses are much higher and errors in dose calculation can result in undertreatment or irreversible damage to healthy tissues.

In radionuclide therapy, the aim is to destroy the tumor while minimizing the toxicity to the normal tissues. Therefore, we have to estimate the biological effects of the radiation on the normal tissues and the tumor.

Suppose that a piece of tissue, consisting of cells, is being irradiated with a particular dose rate . And assume also that this dose rate kills on average a fraction per unit of time. Then at any time , the expected number of dying cells per unit of time would equal

After irradiating that tissue for a finite time , the expected number of surviving cells will be

Assuming that can vary as a function of time, this generalizes to

If we assume that is proportional to the dose rate , we can write

where is the total dose accumulated at time . The exponent is called the Biologically Effective Dose or BED. The value is the fraction of surviving cells.

However, it has been observed that the BED depends non-linearly on the dose. This can be explained intuitively as follows. Radiation damages the tissue mostly by ionizing DNA molecules. It is possible that a single hit by a photon or electron produces so much damage to a DNA molecule that the cell dies. But it is also possible (and more likely) that a single hit produces an error in the DNA that can still be repaired. However, this sublethal damage could become lethal, if that same DNA molecule would be hit a second time during the same treatment. Assuming a sublethal hit is more likely than a lethal one, and that the probability of hitting the same location more than two times is very small, the cell killing could be well approximated as

The first term corresponds to a single lethal hit at time . The second corresponds to the lethal combination of two sublethal hits, one which happened between 0 and , and the second one at time . [2]

Integration over time produces

This expression can be further refined to include also the effect of repair mechanisms. After sublethal damage, the cell may be able to undo that damage, in which case it would survive a second sublethal hit. Assume for convenience that the probability of repair is constant over time, such that a fraction μ of the damaged cells heal themselves per unit of time. Then if cells took a sublethal hit at time , only of them would still be damaged at time . Adjusting equation (13) accordingly produces

The G-factor is called the Lea-Catcheside factor (after the authors who derived these equations). It is easy to check that with {math}\mu = 0, i.e. no cell repair, equation (15) reduces to (13). Fortunately, normal cells are typically better at repairing radiation damage than tumor cells.

Dosimetry software¶

Several software tools have been developed and commercialized to support dosimetry calculations. The first tools (e.g. Olinda/EXM, [3] focused on dosimetry for diagnostic imaging procedures. This kind of software takes as input the activity values in organs at a few different time points, and provides

pre-computed S-values based on anatomical models, such as in Figure 2 (and listed in MIRD pamphlet 11), for many radionuclides, and

software for fitting kinetic models, typically a sum of exponentials, which are used to interpolate between the time points and extrapolate to infinity in a sensible way.

The output is the dose in mGy to all organs, and the corresponding effective dose in mSv.

Some research teams share their more recent software tools for personalized internal dosimetry. An example is the LundaDose Program from Lund University, Sweden. This program focuses on internal dosimetry for therapy with 177Lu or 90Y labeled molecules. It takes SPECT/CT images as input and computes the organ and tumor doses with Monte Carlo simulation. Other similar free software packages can be found at mirdsoft.org, www.idac-dose.org and www.opendose.org.

By taking directly the images of the activity distribution as input, the need for segmenting the source organs is eliminated. The Monte Carlo simulation can make use of the activity in each voxel, or in other words, each voxel is treated as a source region . And similarly, the dose can be computed in each voxel. This is called voxelized dosimetry. It is not only more convenient, it is also more accurate, because it eliminates the need for assuming a uniform activity distribution within large source and target regions. For the final analysis of the dose images, still organ and lesion segmentation is necessary for the target regions , because we need to know where the tumor and the radiosensitive organs are. However, the analysis of the dose in regions can now be made more informative, by taking into account the non-uniform dose distribution in the region.

Examples¶

Annual effective dose due to natural 40K¶

40K is a naturally occurring radioactive isotope of potassium. Its abundance, i.e. the amount of 40K in natural K, is 0.012%. Humans have approximately 2 g K per kg body weight. The half life of 40K is years. It decays by emission with a branching ratio of 90%, see Figure 3. The mean energy of the emitted electron equals 0.59 MeV.

Figure 3:Decay scheme of 40K.

To compute the radiation dose due to 40K, we assume that this dose is only due to the emission. Suppose there are 40K atoms in a g at time . Then the number of radioactive atoms at time equals

implying that the activity, i.e. the number of decaying atoms per unit of time equals

where we have to express in seconds to obtain a result in Bq. Denoting the number of seconds per year as , we have .

Avogadro’s number equals atoms/mole, and 1 mole of weighs 40 g. Consequently, the activity per kg tissue equals

This produces an activity per mass in Bq/kg. In 90% of these decays, an electron is emitted which deposits on average an energy of 0.59 MeV. Thus, the energy deposited by a decay equals

Multiplying and produces the deposited energy per mass and per s in J / (kg s) = Gy / s. Finally, we multiply this with the number of seconds per year and with 1000 to obtain the result in mGy per year:

This calculation seems OK, since the UNSCEAR 2008 report gives also 0.17 mSv for the effective dose from natural 40K irradiation.

Thyroid therapy with 131I¶

The thyroid has a strong affinity for iodine, and thyroid tumors inherit this affinity from the normal cells. Consequently, a beta-emitting isotope like 131I is a good radionuclide for treating thyroid cancer. As can be seen in Table 1, 131I not only emits electrons, but also several gammas. This has the drawback that the radionuclide trapped in the tumor will not only irradiate the tumor with electrons, it will also send some energy to the entire body as photons. But an advantage of these photons is that they can be used for imaging with a gamma camera or activity estimations with a gamma detector. Because several of these gammas have high energies, imaging must be done with high energy collimators, and detectors targeting the thyroid must be well shielded to avoid contributions from 131I uptake in the rest of the body.

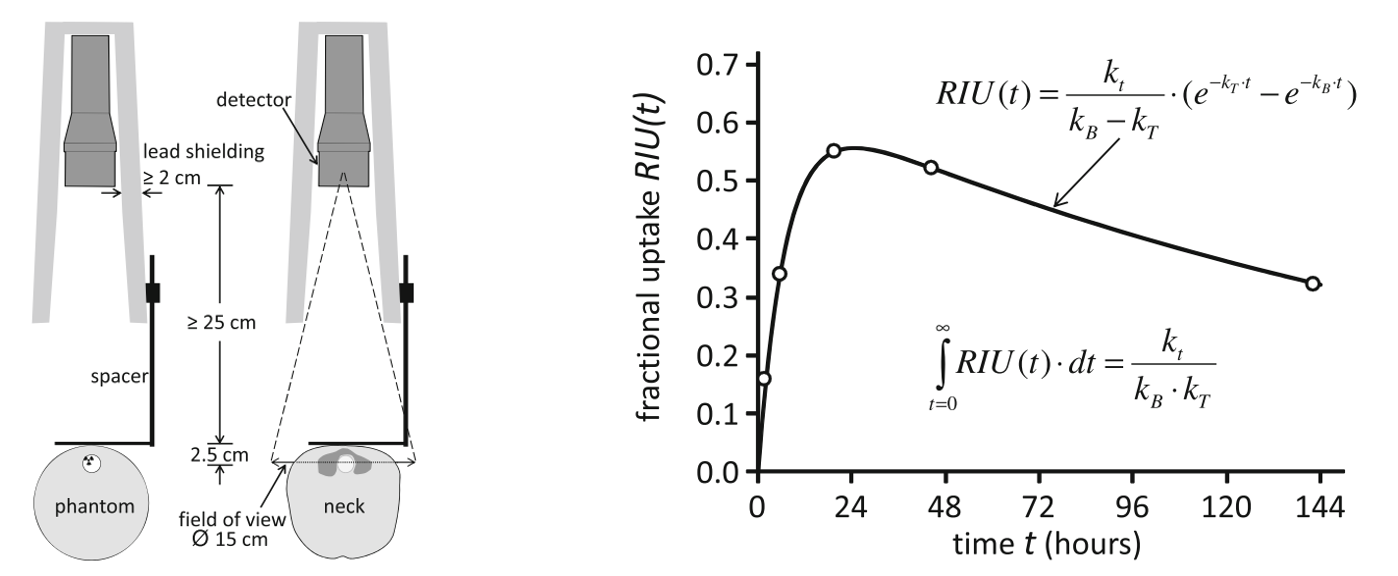

To determine the activity to be administered, a low activity of 131I is administered and imaging is performed to see which fraction of the activity is taken up in the thyroid. For therapy follow up, imaging (or photon counting) is be done to monitor the 131I uptake in the thyroid as a function of time.

Figure 4 illustrates the calibration and activity monitoring with a photon counting detector (typically a NaI crystal with PMT). A standard setup is used to scan the patient, to ensure good reproducibility, such that after calibration the measurement is quantitative. For calibration, a phantom mimicking the geometry and attenuation of the neck is used, containing 131I at the position of the thyroid.

Figure 4:Thyroid therapy with I. At different time points, activity measurements are done with a simple detector, calibrated with a phantom. A tracer kinetic model is applied to estimate the time activity curve from a few measurements. The figures are from H. Hänscheid & Heribert, et al. (2013). (RIU(t) denotes fractional I uptake in the target tissue at time t, and , and are time constants of the kinetic model.)

With this setup, the patient is scanned a few times over a week, producing measurements of the activity in the thyroid. Then a kinetic model is applied, to fit a smooth and realistic time-activity curve through these points. A good model must be used, because estimating the total dose to the thyroid involves a very strong extrapolation beyond the last time point (see Figure 4).

131I-mIBG therapy for neuroblastoma¶

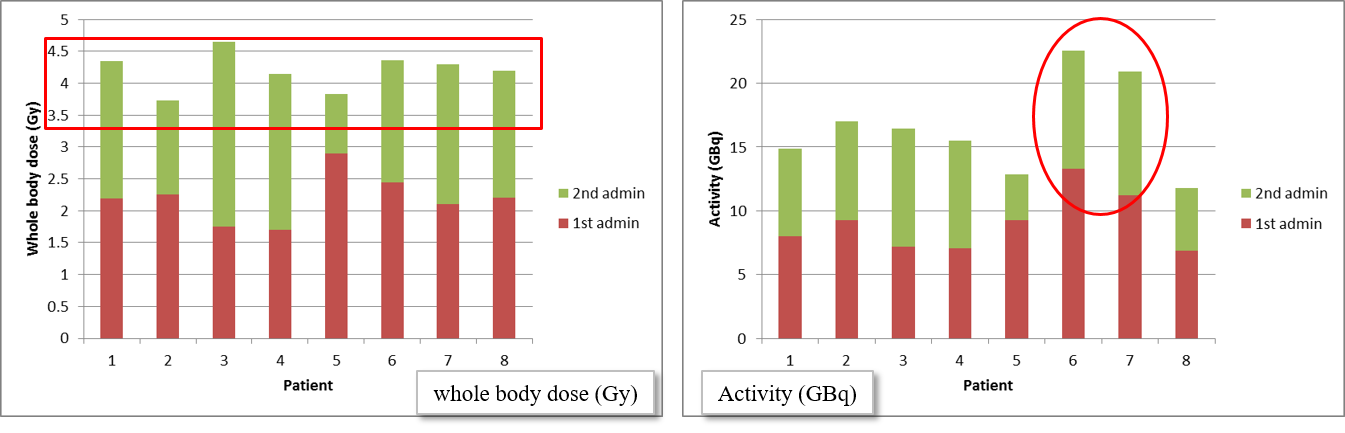

The compound mIBG (meta-iodobenzylguanidine) is taken up by cells of the sympathetic nervous system. Neuroblastoma usually inherit this affinity for mIBG, and as a result, 131I-mIBG can be used to selectively irradiate these tumors. To circumvent the toxic effects on the bone marrow (which makes red blood cells), stem cells are collected before treatment and reinfused after the treatment. This will ensure the production of blood cells after treatment. The 131I-mIBG treatment is combined with Topotecan, a drug that makes neuroblastoma more sensitive to radiation M.N. Gaze, et al. (2005).

The aim of the 131I-mIBG procedure, applied to treat children with metastatic neuroblastoma, is to achieve a whole body dose of 4 Gy. It has been shown that with this whole body dose, the dose to the neuroblastoma is sufficiently high and side effects are limited. To achieve this, the therapy is given in two fractions. The first fraction delivers a first whole body dose well below 4 Gy. In addition, the photons emitted by 131I are used to determine the whole body dose. This is often done with a simple gamma detector and appropriate calibration, similar to what is shown in Figure 4, but this time focusing on the entire body. Alternatively (and more accurately), planar imaging or SPECT can be used. From that measured dose and the known amount of administered activity in the first fraction, the amount of activity for the second fraction is computed, to obtain the target dose of 4 Gy.

Figure 5:The whole body doses achieved in 8 patients (left), and the activity that was administered to obtain this dose of approximately 4 Gy (right). The red and green blocks correspond to the first and second fraction, respectively. For patients 6 and 7, much more activity was needed to achieve the same whole body dose. Courtesy of Gaze et al. B. Sangro et al. (2012).

Figure 5 shows for 8 patients the whole body doses produced by the two fractions. The dose of the first fraction was only based on the patient weight, and produced roughly 2 Gy. This was used to adjust the activity given in the second fraction, shown in the plot at the right hand side in the figure. The plot at the left shows that this produced a total dose of approximately 4 Gy. This treatment is effective. However, more accurate tumor dose computation would be useful, to provide more information about the relation between the administered doses, the tumor control and the toxic effects to healthy tissues, which would facilitate the development of even more effective, personalized treatment.

90Y selective internal radiation therapy for liver tumors¶

The liver can be affected by a primary liver (hepatic) tumor or by tumor metastases originating from elsewhere in the body.

One approach to treating liver tumors is radioembolization, i.e. to release small radioactive spheres into the blood supplying the tumors. These microspheres, made of resin or glass, have a diameter of 25-35 μm, which is small enough to travel through larger blood vessels, and big enough to get stuck in the tumor micro-vasculature. The microsphere then hinders or blocks the perfusion through the microvessel, which is already bad for the tumor. But more importantly, these microspheres contain a β-emitting isotope. The emitted electrons interact with the surrounding tissue, depositing their energy within a few mm from where they are emitted. The aim is to have the microspheres accumulated in or very close to the tumor lesions, such that the β-radiation destroys the tumor with minimal damage to the healthy liver.

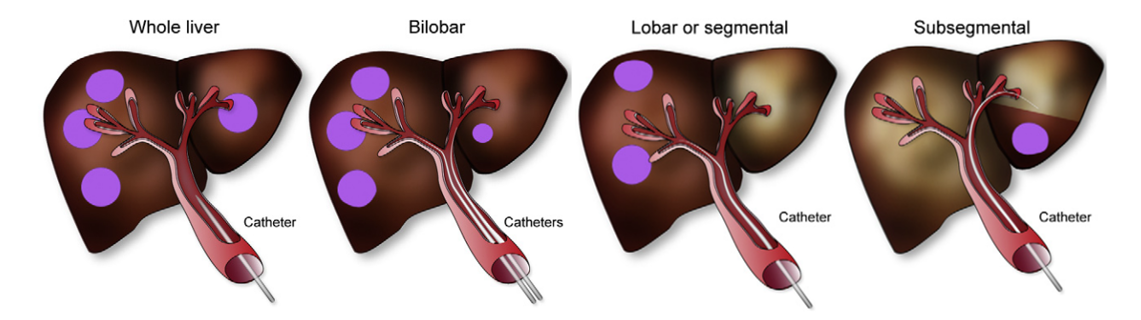

The liver is perfused not only by the hepatic artery, but also by the portal vein. Veins are typically outputting blood from organs, but the liver takes input from a vein too, because its task involves processing venous blood from the stomach, intestines and spleen. Healthy liver cells receive about 75% of their blood from the portal vein, and only 25% from the hepatic artery. In contrast, tumors take most of their blood from the hepatic artery. For that reason, the microspheres are released via a catheter that is maneuvered into the hepatic artery. To further increase selectivity, the catheter is steered into one or a few branches of the hepatic artery which are known to supply tumors. As illustrated in Figure 6, a better healthy tissue sparing can be achieved when the tumor is more localized in the liver. For this reason, the treatment is called selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT).

Figure 6:Radioactive microspheres are sent into the liver through selected branches of the portal vein, targeting the tumors. B. Sangro et al. (2012).

One of the electron-emitting isotopes that is often used for SIRT is the yttrium isotope 90Y.

Dose verification for SIRT with 90Y microspheres¶

As shown in Table 1, 90Y is really a pure β-emitter, but in 32 of each million decays, it produces a positron. Obviously, it is a poor positron emitter, but because the treatment involves large doses (a few GBq), because the microspheres are concentrated near the liver tumors and because the effective sensitivity of current PET systems is high, it is possible to make quantitative images of the 90Y distribution in the body of the patient. Since the microspheres remain trapped for a long time in the microvessels, we can assume that the microspheres concentrations remain constant over time, and that the radioactive decay of 90Y is the only cause of change to the activity concentration. Therefore, we only need a single PET image for dose verification after treatment.

Since the electrons deposit their energy very close to their emission source, the radiation dose to the tissues can be computed using the “local deposition model”. That means that with good approximation, the dose is proportional to the activity concentration achieved shortly after injection: multiplication with a global scale factor transforms the PET activity image with voxel values in Bq/ml to a dose image with voxel values in Gy.

The time integrated activity equals

where is the activity in Bq in a particular region of interest, and = 64.1 hours is the half life of 90Y. Following equation (5), the dose is obtained by multiplying with the S-factor, given by equation (2). For 90Y, the S-factor reduces to

where is the mass of the region and is the average energy of the emitted electron. Consequently, the accumulated dose in a particular region equals

Consequently, an activity of 1 GBq 90Y trapped in a region of 1 kg produces an accumulated radiation dose of approximately 50 Gy.

An image in Bq/ml can be converted to an image in Bq/g by dividing it by the tissue density in g/ml, which is close to unity except for bone and lung. An 90Y activity image in Bq/g can be converted to accumulated dose in Gy, by multiplying it with Js • 1000 g/kg = Gy g s.

SIRT treatment planning with 99mTc labeled micro-aggregated albumin¶

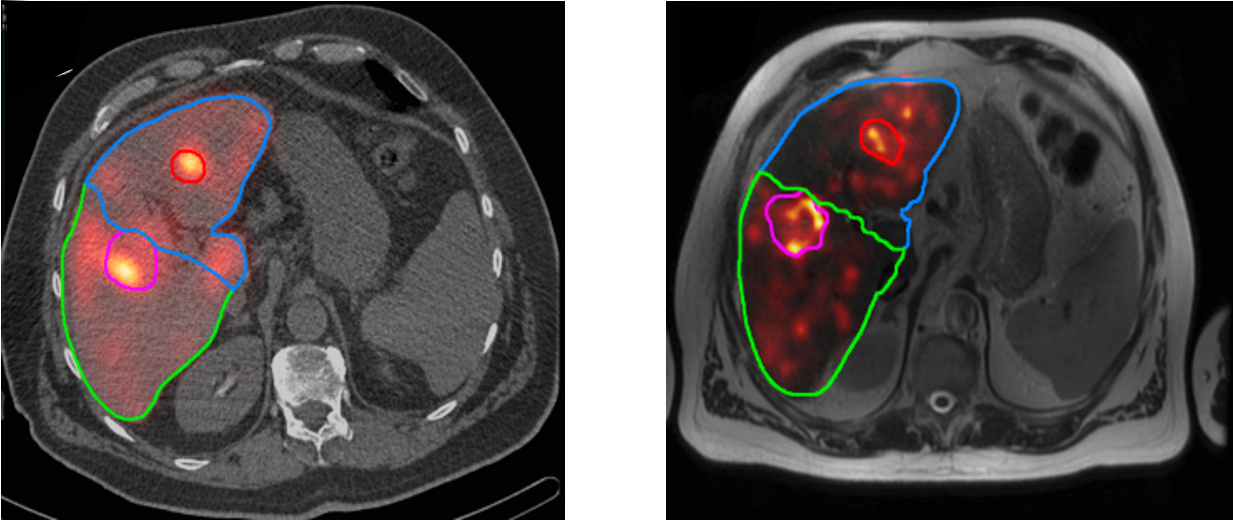

Albumin microaggregates (MAA) are very small particles (a few microns) which tend to accumulate in microvasculature, much like resin or glass microspheres. MAA labeled with 99mTc are used to simulate a SIRT treatment: the 99mTc-MAA is released in selected branch(es) of the portal vein, and the result is imaged with SPECT. SPECT imaging must be done shortly after MAA-administration, because unlike the therapeutic microspheres, MAA is only trapped temporally. The 99mTc-MAA study is done to check if the injected particles will remain in the liver, or if a significant portion of them ends up in the lungs. In some patients this happens, because their vasculature has some liver-to-lung shunts. The study is also done to verify that the catheterization procedure will reach all the tumors. Figure 7 shows transaxial slices from a pre-treatment 99mTc-MAA image and the corresponding post-treatment 90Y-PET image. In this study, a good agreement between the pre- and post-treatment images was obtained.

Figure 7:Left: the 99mTc-MAA image (in color) fused with the corresponding CT image (black and white), from the pre-treatment SPECT/CT image. Right: the 90Y-PET image fused with the corresponding MR image, from the post-treatment PET/MR image.

Quantitative imaging¶

Treatment planning and dose verification require quantitative imaging, since we need activity images in Bq/ml to compute dose images in Gy. The creation and analysis of accurate dose images is not only useful to verify if the treatment was successful, it also provides valuable data to learn more about the complicated relationship between radiation dose and biological effect, both in the tumors and the normal tissues. This new knowledge should enable us to make radionuclide therapy more effective. Doing that will require more accurate treatment planning, and therefore also quantitative imaging.

As explained in previous chapters, PET and SPECT are quantitative, provided that

all corrections for sensitivity, attenuation, Compton scatter and/or randoms are performed well.

the reconstructed image values are calibrated by determining the calibration factor, which converts the reconstructed voxel values into values in Bq/ml, see sections Quantification for SPECT and Quantification for PET. The calibration factor is radionuclide dependent, and in particular in SPECT, this dependence is so complicated that it necessitates determining the calibration factor from phantom measurements for each tracer.

In 2009, the MIRD committee adopted a standardization of nomenclature (Journal of Nuclear Medicine, 2009; 50: 477-484)..

Organ Level INternal Dose Assessment & EXponential Modeling developed by Vanderbilt University, TN, USA and recently commercialized)

- James E. Martin. (2006). Physics for Radiation Protection: A Handbook. John Wiley.

- H. Hänscheid, & Heribert, et al. (2013). EANM Dosimetry Committee Series on Standard Operational Procedures for Pre-therapeutic Dosimetry II. Dosimetry Prior to Radioiodine Therapy of Benign Thyroid Diseases. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, 40, 1126–1134.

- M.N. Gaze, et al. (2005). Feasibility of Dosimetry-based High-dose 131I-meta-iodobenzylguanidine with Topotecan as a Radiosensitizer in Children with Metastatic Neuroblastoma. Cancer Biotherapy and Radiopharmaceuticals, 20(2), 195–199.

- B. Sangro, M. Iñarrairaegui, & J.I. Bilbao. (2012). Radioembolization for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Journal of Hepatology, 56(2), 464–473.