Radiation which interacts with electrons can affect chemical bonds in DNA, and as a result, cause damage to living tissues. The probability that an elementary particle will cause an adverse ionisation is proportional to the energy of the particle deposited in the tissue. In addition, the damage done per unit energy depends on the type of particle.

In diagnostic nuclear medicine, the aim is of course to obtain diagnostic images without or with minimum damage to the patient. Consequently, the amount of activity administered to the patient should be as low as reasonably achievable (ALARA). “Reasonably achievable” means that the radiation emitted by the tracer should still be sufficient to make valuable clinical images.

The amount of radiation deposited in an object is expressed in gray (Gy). A dose of 1 gray is defined as the deposition of 1 joule per kg absorber:

To quantify (at least approximately) the amount of damage done to living tissue, the influence of the particle type must be included as well. E.g. it turns out that 1 J deposited by neutrons does more damage than the same energy deposited by photons. To take this effect into account, a quality factor is introduced. Multiplication with the quality factor converts the dose into the dose equivalent. Quality factors are given in Table 1.

Table 1:Quality factor converting dose in dose equivalent (ICRP2007).

Radiation | Q |

X-ray, γ-ray, | 1 |

electrons, positrons | 1 |

protons | 2 |

neutrons | 2.5 ... 22, depending on energy |

α-particals | 20 |

The dose equivalent is expressed in Sv (sievert). Since for photons, electrons and positrons, we have 1 mSv per mGy in diagnostic nuclear medicine. The natural background radiation is about 2 mSv per year, or about 0.2 μSv per hour.

The older units for radiation dose and dose equivalent are rad and rem:

When the dose to every organ is computed, one can in addition compute an “effective dose”, which is a weighted sum of organ doses. The weights are introduced because damage in one organ is more dangerous than damage in another organ. The most sensitive organs are the gonads (weight about 0.25), the breast, the bone marrow and the lungs (weight about 0.15), the thyroid and the bones (weight about 0.05), see Table 2. The sum of all the weights is 1. The weighted average produces a single value in mSv. The risk of death due to tumor induction is about 5% per “effective Sv” according to report ICRP-60 (International Commission on Radiological Protection (http://www.icrp.org)), but it is of course very dependent upon age (e.g. 14% for children under 10). Research in this field is not finished and the tables and weighting coefficients are adapted every now and then.

Table 2:Organ weight factors to compute the effective dose (ICRP 103, 2007).

organ | weight | total |

red marrow, colon, lungs, stomach, breast | 0.12 | 0.60 |

gonads | 0.08 | 0.08 |

bladder, liver, esophagus, thyroid | 0.04 | 0.16 |

brain, skin, salivary glands, bone surfaces | 0.01 | 0.04 |

remainder (adrenals, extrathoracic region, gallbladder, heart, kidneys, lymphatic nodes, muscle, oral mucosa, pancreas, prostate, small intestine, spleen, thymus, uterus/cervix) | 0.00923 | 0.12 |

total | 1 |

To obtain the dose equivalent delivered by one organ to another organ (or to itself, in which case ), we have to make the following computation:

- is the dose equivalent;

- denotes a particular emission. Often, multiple photons or particles are emitted during a single radioactive event, and we have to compute the total dose equivalent by summing all contributions;

- is the quality factor for emission

- is the total number of particles emitted in organ

- is the probability that a particle emitted in organ will deposit (part of) its energy in organ

- is the (average) energy that is carried by the particles and that can be released in the tissue. For electrons and positrons, this is their kinetic energy. For photons, it is all of their energy.

- is the mass of organ .

In the following paragraphs, we will discuss these factors in more detail, and illustrate the procedure with two examples.

The particle ¶

The ideal tracer for single photon emission would emit exactly one photon in every radioactive event. However, most realistic tracers have a more complex behaviour. Some of them emit several photons at different energies and in different quantities. For example, Iodine-123 has several different ways of decaying (via electron capture) from I into Te. Each decay scheme produces its own set of photons. Most of these schemes share an energy jump of 159 keV, and the mean number of 159 keV photons emitted per desintegration equals 0.836. In some of the decay schemes, there is an internal conversion electron with an average energy of 127 keV, that comes with a probability of 0.134 per desintegration. In total, I uses combinations of 14 different gamma rays, 5 x-rays, 3 internal conversion electrons and 5 Auger electrons to get rid of its excess energy. Each of those has its own probability. In principle, we need to include them all, but it usually suffices to include only the few dominating emissions.

The total number of particles ¶

The number of particles emitted per s changes with time. Due to the finite half life, the radioactivity decays exponentially (see equation (6)). Moreover, the distribution of the tracer molecule in the body is determined by the metabolism, and it changes continuously from the time of injection. Often, the tracer molecule is metabolized: the molecule is cut in pieces or transformed into another one. In those cases, the radioactive atoms may follow one or several metabolic pathways. As a result, it is often very difficult or simply impossible to accurately predict the amount of radioactivity in every organ as a function of time. When a new tracer is introduced, the typical time-activity curves are mostly determined by repeated emission scans in a group of subjects.

Assuming that we know the amount of radioactivity as a function of time, we can compute the total number of particles as

where is the number of particles emitted per s at time . For some applications, it is reasonable to assume that the tracer behaviour is dominated by its physical decay. Then we have that

Here is the number of particles or photons emitted per s at time 0, and is the half life. For a source of 1 MBq at time 0, per s, since 1 Bq is defined as 1 emission per s.

Often, the tracer is metabolized and sent to the bladder, which implies a decrease of the tracer concentration in most other organs. Therefore, the amount of radioactivity decreases faster than predicted by (6) in these organs. One way to approximate the combined effect of metabolism and physical decay could be to replace the physical half life with a shorter, effective half life in (6). In other cases, it may be necessary to integrate the measured time activity curves numerically.

The probability ¶

This probability depends on the geometric configuration of the organs and on the attenuation coefficients. The situation is very different for photons on the one hand and electrons and positrons on the other. As illustrated by Table 2 for positrons, the mean path length of an electron and positron in tissue is very short, even for relatively high kinetic energies. Consequently, for these particles, is close to 1, while is negligible for different organs and . The probability that a photon travels from A to B depends on the attenuation along that trajectory. Similarly the probability that it deposits all or a part of its energy in B depends on the attenuation coefficient in organ B.

The energy ¶

As mentioned above, denotes kinetic energy for electrons and positrons, and the total amount of energy for photons. This energy is usually given in electronvolt. However, to compute the result in Gy, we need the energy in joule. The eV is defined as the amount of energy acquired by an electron if it is accelerated in an electrical field of 1 V. Because joule equals coulomb times volt, we have that

Example 1: single photon emission¶

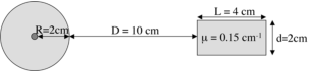

Consider the configuration shown in Figure 1. Assume that the point source in the left box contains 1 MBq of the isotope 123I. As discussed before, this isotope has a very busy decay scheme, but we will assume that we can ignore all emissions except the following two:

Gamma radiation of 159 keV, with an abundance of 0.84,

Conversion electron of 127 keV, with an abundance of 0.13.

The half life of 123I is 13.0 hours. The boxes are made of plastic or something like that, with an attenuation coefficient of 0.15 cm-1 for photons with energy of 159 keV. The density of the boxes is 1 kg/liter. The boxes are hanging motionless in air, the attenuation of air is negligible. Our task is to estimate the dose that both boxes will receive if we don’t touch this configuration for a few days.

Figure 1:Two objects, one with a radioactive source in the center. The size of the right box is 2 × 2 × 4 cm3.

We are going to need the mass of the boxes. For the left box we have:

and for the right box:

Because a few days lasts several half lifes, a good approximation is to integrate until infinity using equation (6). Consequently, the total number of desintegrations is estimated as

This number must be multiplied with the mean number of particles per desintegration:

number of photons is 0.84 N = 5.67 × 1010\

number of electrons is 0.13 N = 8.78 × 109

The radius of the left box is large compared with the mean path length of the electrons, so the box receives all of their energy: . Thus, the dose of the left box due to the electrons is:

For the photons, the situation is slightly more complicated, because not all of them will deposit their energy in the box. Because the box is spherical and the point source is in the center, the amount of attenuating material seen by a photon is the same for every direction. With equation (5) we can compute the probability that a photon will escape without interaction:

Thus, there is a chance of 1 - 0.74 = 0.26 that a photon will interact. This interaction could be a Compton event, in which only a part of the photon energy will be absorbed by the box. This complicates the computations considerably. To avoid the problem, we will go for a simple but pessimistic solution: we simply assume that every interaction results in a complete absorption of the photon. That yields for the photon dose to the left box:

So the total dose to the left box equals about 16 mGy.

For the right box, we can ignore the electrons, they cannot get out of the left box. We already know that a fraction of 0.74 of the photons escapes the left box. Now, we still have to calculate which of those will interact with the right box. We first estimate the fraction traveling along a direction that will bring it into the right box. When observed from the point source position, the right box occupies a solid angle of approximately {math}d^2 / (D + R)^2. The total solid angle equals , so the fraction of photons travelling towards the right box equals

These photons are travelling approximately horizontally, so most of them are now facing 4 cm of attenuating material. Applying the same pessimistic approach as above yields the fraction that interacts with the material of the right box:

Combining all factors yields then number of photons interacting with the right box:

Finally, multiplying with the energy and dividing by the mass yields:

This is much less than the dose of the left box. The right box is protected by its distance from the source!

Example 2: positron emission tomography¶

Here, we study the same setup of Figure 1, but now with a point source containing 1 MBq of 18F. This is a positron emitter. From Table 2, we know that the average kinetic energy of the positron is 250 keV. Most of this energy is dissipated in the tissue before the positron annihilates. Thus, there are three contributions to the dose of the left box: the positron and the two photons. The right box can at most be hit by one of the photons.

We assume that in every desintegration, exactly one positron is produced, which annihilates with an electron into two 511 keV. At 511 keV, the attenuation of the boxes is 0.095 cm-1. The half life of 18F is 109 minutes.

The total number of desintegrations is

Proceeding in the same way as above, we find the following doses:

The total dose then equals = 18.8 mGy.

For the right box, we first estimate the number of interacting photons (remember that there are two photons per desintegration):

And for the dose to the right box we get:

Internal dosimetry calculations¶

Internal dosimetry calculations use the same principle as in the examples above to compute the dosage to every organ. Because there are many organs, and because the activity in any organ contributes to the dose in any other organ, the computations are complex and tedious. This is one of the reasons why dedicated software has been developed. With the fast computers we have today, the calculations can be carried out more accurately. E.g. it is possible to take the effects of Compton scatter into account using Monte Carlo techniques.

Of course, we still have to provide a meaningful input to the software. In principle, we should input the precise anatomy of the patient. Because this is usually not available, this problem is avoided by using a few standard geometries, which model the human anatomy, focussing on the most senstive organs. It follows that the resulting doses should only be considered as estimates, not as accurate numbers.

We also have to provide the tracer concentration as a function of time for all organs. For known tracers, the software may contain typical residence times; for new ones, measurements in humans have to be carried out to estimate the dosimetry.