In principle, PET and SPECT have the potential to provide quantitative images, that is pixel values can be expressed in Bq/ml. This is only possible if the reconstruction is based on a “sufficiently accurate” model, e.g. if attenuation is not taken into account, the images are definitely not quantitative. It is difficult to define “sufficiently accurate”, the definition should certainly depend upon the application. Requirements for visual inspection are different from those for quantitative analysis.

In image analysis often regions of interest (ROI’s) are used. A region of interest is a set of pixels which are supposed to belong together. Usually, an ROI is selected such that it groups pixels with (nearly) identical behavior, e.g. because they belong to the same part of the same organ. The pixels are grouped because the relative noise on the mean value of the ROI is lower than that on the individual pixels, so averaging over pixels results in strong noise suppression. ROI definition must be done carefully, since averaging over non-homogeneous regions leads to errors and artifacts! Ideally an ROI should be three-dimensional. However, mostly two dimensional ROI’s defined in a single plane are used for practical reasons (manual ROI definition or two-dimensional image analysis software).

In this chapter only two methods of quantitative analysis will be discussed: standard uptake values (SUV) and the use of compartmental models. SUV’s are simple to compute, which is an important advantage when the method has to be used routinely. In contrast, tracer kinetic analysis with compartmental models is often very time consuming, but it provides more quantitative information. In nuclear medicine it is common practice to study the kinetic behavior of the tracer, and many more analysis techniques exist. However, compartmental modeling is among the more complex ones, so if you understand that technique, learning the other techniques should not be too difficult. The book by Cherry, Sorenson and Phelps SR Cherry et al. (2012) contains an excellent chapter on kinetic modeling and discusses several analysis techniques.

Standardized Uptake Value¶

The standardized uptake value provides a robust scale of tracer amounts. It is defined as:

To compute it, we must know the total dose administered to the patient. Since the total dose is measured prior to injection, and the image is produced after injection, we must correct for the decay of the tracer in between. Moreover, the tracer amounts are measured with different devices: the regional tracer concentration is measured with the SPECT or PET, the dose is measured with a radionuclide calibrator. Therefor, the sensitivity of the tomograph must be determined. This is done by acquiring an image of a uniform phantom filled with a know tracer concentration. From the reconstructed phantom image we can compute a calibration factor which converts “reconstructed pixel values” into Bq/ml (see section Quantification).

A SUV of 1 means that the tracer concentration in the ROI is identical to the average tracer concentration in the entire patient body. A SUV of 4 indicates markedly increased tracer uptake. The SUV-value is intended to be robust, independent from the administered tracer amount and the mass of the patient. However, it changes with time, since the tracer participates in a metabolic process. So SUVs can only be compared if they correspond to the same time after injection. Even then, one can think of many reasons why SUV may not be very reproducible, and several publications have been written about its limitations. Nevertheless, it works well in practice and is used all the time.

The SUV is a way to quantify the tracer concentration. But we don’t really want to know that. The tracer was injected to study a metabolic process, so what we really want to quantify is the intensity of that process. The next section explains how this can be done. Many tracers have been designed to accumulate as a result of the metabolic process being studied. If the tracer is accumulated to high concentrations, many photons will be emitted resulting in a signal with good signal to noise ratio. In addition, although the tracer concentration is not nicely proportional to the metabolic activity, it is often an increasing function of that activity, so it still provides useful information.

Tracer kinetic modeling¶

Introduction¶

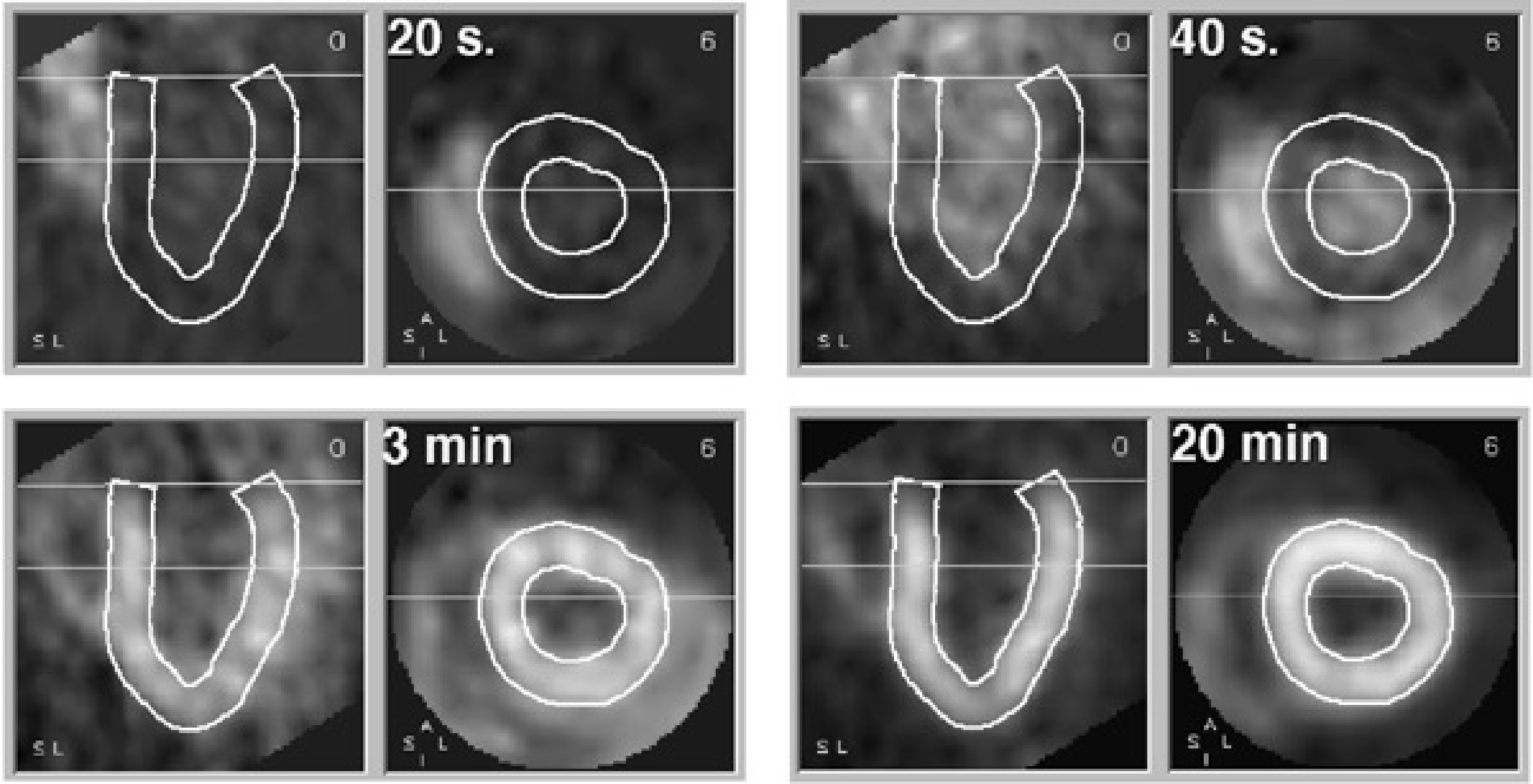

Figure 1:Four samples from a dynamic study. Each sample shows a short axis and long axis slice through the heart. The wall of the left ventricle is delineated. 20 s after injection, the tracer is in the right ventricle. At 40 s it arrives in the left ventricle. At 3 min, the tracer is accumulating in the ventricular wall. At 20 min, the tracer concentration in the wall is increased, resulting in better image quality.

The evolution of the tracer concentration as a function of time can be imaged with PET (or SPECT) using “dynamic acquisition”. Instead of creating a single image, a series of images is created, typically starting at the time of tracer injection and continuing for 30 - 90 minutes, depending on the tracer and the kinetic model that is used to analyse the results.

The evolution of the tracer concentration with time in a particular point (pixel) depends on the tracer and on the characteristics of the tissue in that point. Figure 1 shows the evolution of radioactive ammonia 13NH3 (recall that 13N is a positron emitter) in the heart region. This is a perfusion tracer: its concentration in tissue depends mainly on blood delivery to the cells. The tracer is injected intravenously, so it first shows up in the right atrium and ventricle. From there it goes to the lungs, and arrives in the left ventricle after another 20 s. After that, the tracer is gradually removed from the blood since it is accumulated in tissue. The myocardial wall is strongly perfused, after 20 min accumulation in the left ventricular wall is very high, and even the thin right ventricular wall is clearly visible.

The most important factor determining the dynamic behavior of ammonia is blood flow. However, the ammonia concentration is not proportional to blood flow. To quantify the blood flow in ml blood per g tissue and per s, the flow must be computed from dynamic behavior of the tracer. To do that, we need a mathematical model that describes the most important features of the metabolism for this particular tracer. Since different tracers trace different metabolic processes, different models may be required for different tracer.

The compartmental model¶

The compartments¶

In this section, the three compartment model is described. It is a relatively general model and can be used for a few different tracers. We will focus on the tracer 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG), which is a glucose analog. “Analog” means that it is no glucose, but that it is sufficiently similar to follow, to some extent, the same metabolic pathway as glucose. In fact, it is a better tracer than radioactive glucose, because it is trapped in the cell, while glucose is not. When glucose enters the cell, it is metabolized and the metabolites may escape from the cell. As a result, radioactive glucose will never give a strong signal. In contrast, FDG is not completely metabolized (because of the missing oxide), and the radioactive 18F atom stays in the cell. If the cells have a high metabolism, a lot of tracer will get accumulated resulting in a strong signal (many photons will be emitted from such a region, so the signal to noise ratio in the reconstructed image will be good).

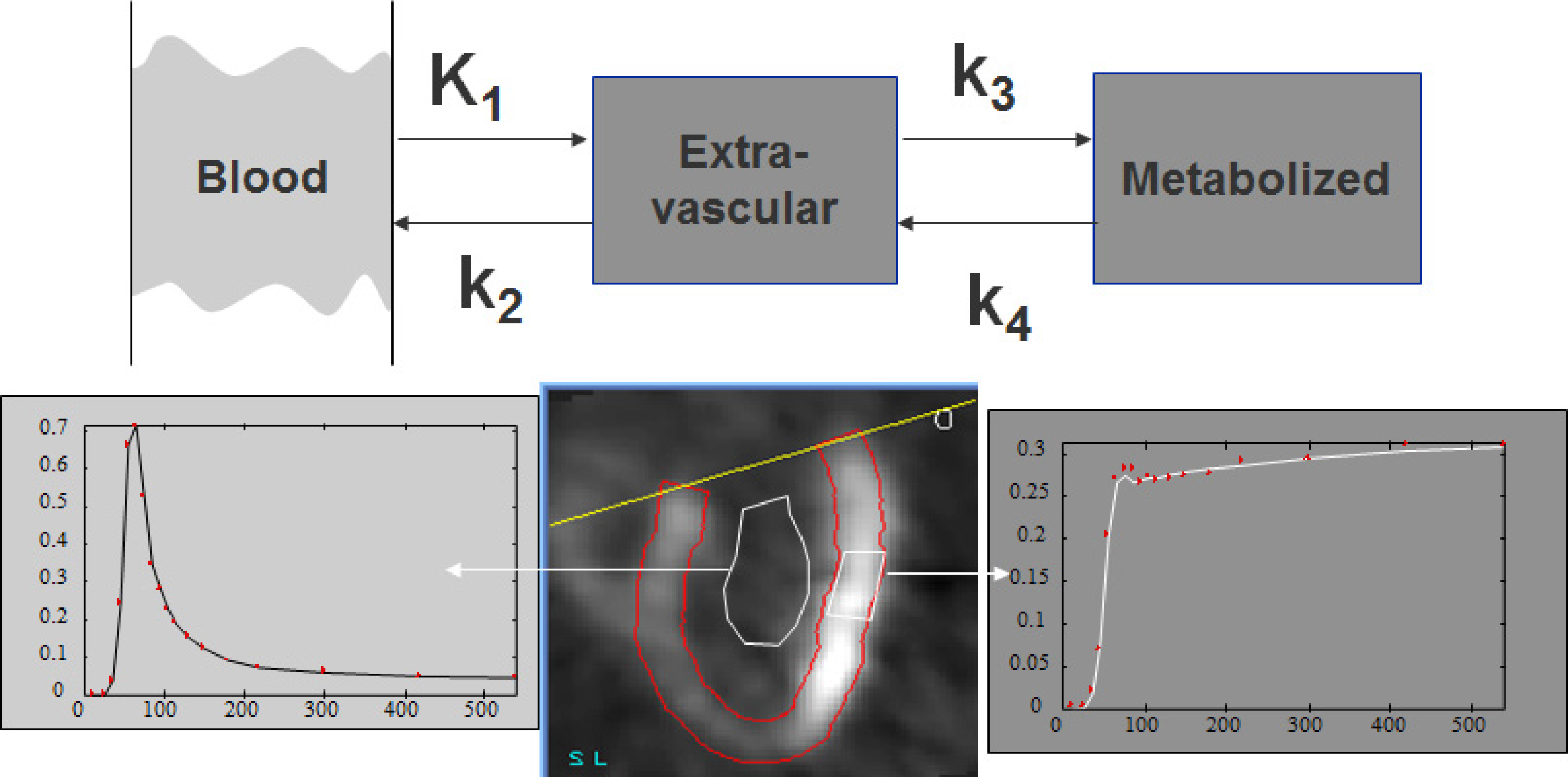

Figure 2:Three compartment model, and corresponding regions in a cardiac study. The first compartment represents plasma concentration (blood pool ROI), the second and third compartment represent the extavascular tracer in original and metabolized form (tissue ROI). For the tissue curve, both the measured points and the fitted curve are shown.

Figure 2 shows the three compartmental model and its relation to the measured concentrations. The first compartment represents the radioactive tracer molecule present in blood plasma. The second compartment represents the unmetabolized tracer in the “extravascular space”, that is, everywhere except in the blood. The third compartment represents the radioactive isotope after metabolization (so it may now be part of a very different molecule). In some cases, the compartments correspond nicely to different structures, but in other cases the compartments are abstractions. E.g., the second two compartments may be present in a single cell. We will denote the blood plasma compartment with index P, the extravascular compartment with index E and the third compartment with index M.

These compartments are an acceptable simplified model for the different stages in the FDG and glucose pathways. A model for another tracer may need fewer or more compartments.

To analyse the tracer concentration curves with the compartmental model, regions of interest (ROI) are drawn in the image and the mean tracer concentration in the ROI as a function of time is extracted to produce the time-activity curves. In Figure 2 a region is drawn inside the left ventricle to obtain the tracer concentration in the blood. A second region is drawn in the left ventricular wall to obtain the tracer concentration in that region of the heart. The model is then applied to analyse how the concentration in the blood influences the concentration in the tissue.

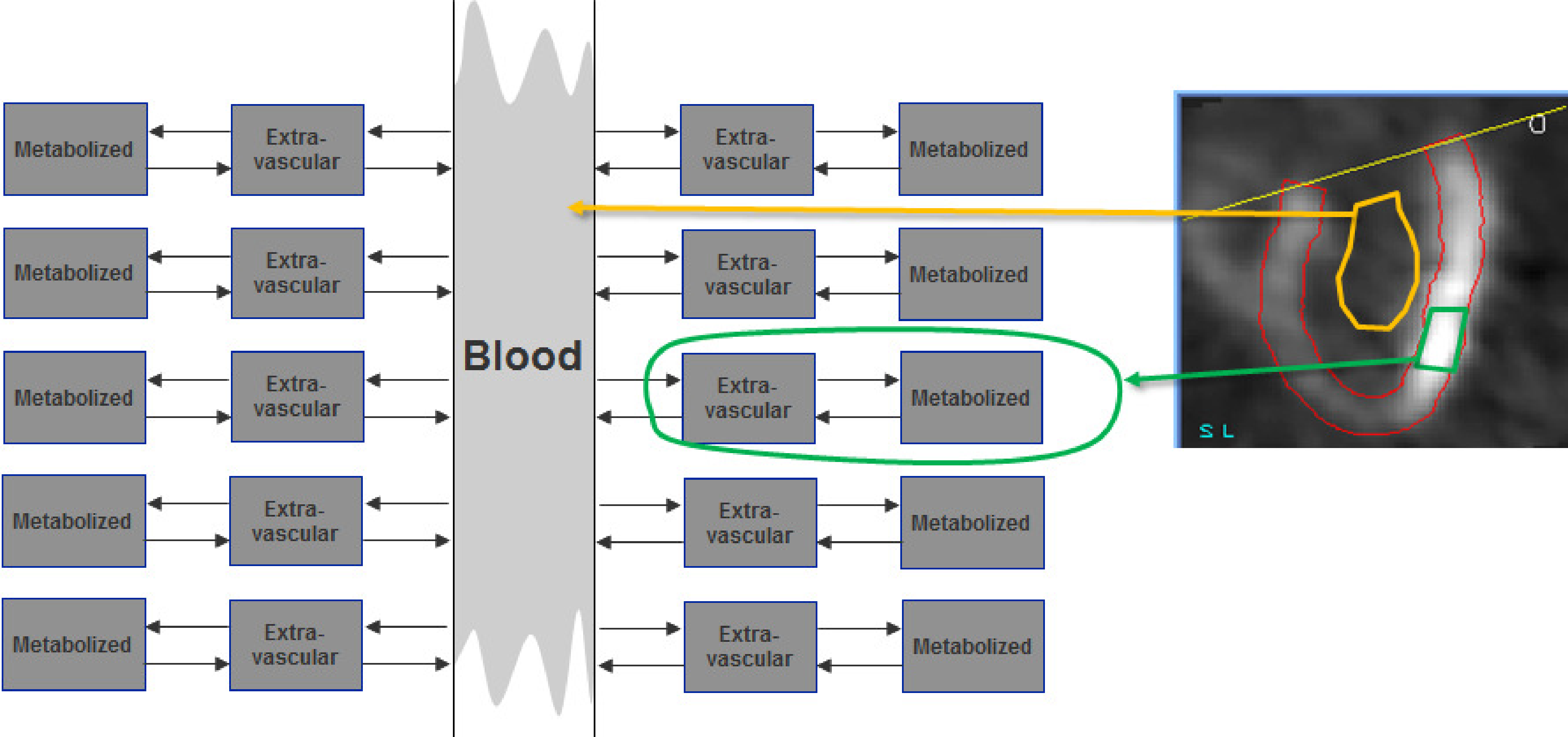

Figure 3:The time-dependent tracer concentration in the blood and the rate constants in the tissue region determine the evolution of the tissue tracer concentration. The blood interacts with a large amount of tissue. Since the tissue region we study is small, its effect on the blood concentration is negligible.

As illustrated in Figure 3, the analysis must explain how the tissue concentration is determined by the blood concentration and the tissue features. In contrast, the blood concentration is essentially independent of the concentration in the region we study. It is determined by the way the tracer is injected and by the tracer exchange with the entire body. The contribution of the small region we study to the blood concentration is negligible compared to the contribution of the entire body.

The rate constants¶

The amount of tracer in a compartment can be specified in several ways: number of molecules, mole, gram or Bq. All these numbers are directly proportional to the absolute number of molecules. If we study a single gram of tissue, the amounts can be expressed in Bq/g, which is the unit of concentration. Remark, though, that these are not tracer concentrations of the compartments, since the gram tissue contains several compartments.

The compartments may exchange tracer molecules with other compartments. It is assumed that this exchange can be described with simple first order rate constants. This means that the amount of tracer traveling away from a compartment is proportional to the amount of tracer in that compartment. The constant of proportionality is called a rate constant. For the three compartment model, there are two different types of rate constants. Constant is a bit different from , and because the first compartment is a bit different from the other two (Figure 2).

The amount of tracer going from the blood plasma compartment to the extravascular compartment is

where is the plasma tracer concentration (units: Bq/ml). is the product of two factors. The first one is the blood flow , the amount of blood supplied in every second to the gram tissue. has units ml/(s g). The second factor is the extraction fraction , which specifies which fraction of the tracer passing by in is exchanged with the second compartment . Since it is a fraction, has no unit. For some tracers, is almost 1 (e.g. for radioactive water). For other tracers it is 0, which means that the tracer stays in the blood. For FDG it is in between. Consequently, the product has units Bq/(s g) and tells how many Bq are extracted from the blood per second and per gram tissue. is a function of the time, is not (or more precisely, we assume it stays constant during the scan). Both and are also a function of position: the situation will be different in different tissue types.

The amount of tracer going from to equals:

where is the total amount of tracer in compartment per gram tissue (units: Bq/g). Constant tells which fraction of the available tracer is metabolized in every second, so the unit of is 1/s. The physical meaning of and is similar: they specify the fractional transfer per second.

The target molecule¶

The tracer is injected to study the metabolism of a particular molecule. It is assumed that the metabolic process being studied is constant during the measurement, and that the target molecule (glucose in our example) has reached a steady state situation. Steady state means that a dynamic equilibrium has been reached: all concentrations remain constant. Steady state can only be reached with well-designed feedback systems (poor feedback systems oscillate), but it is reasonable to assume that this is the case for metabolic processes in living creatures.

Since FDG and glucose are not identical, their rate constants are not identical. The glucose rate constants will be labeled with the letter . The glucose and FDG amounts are definitely different: glucose is abundantly present and is in steady state condition. FDG is present in extremely low concentrations (pmol) and has not reached steady state since the images are acquired immediately after injection.

The plasma concentration is supposed to be constant. We can measure it by determining the glucose concentration in the plasma from a venous blood sample. The extravascular glucose amount is supposed to be constant as well, so the input must equal the output. For glucose, is very small. Indeed, corresponds to reversal of the initiated metabolization, which happens only rarely. Setting to zero we have

Thus, we can compute the unknown glucose amount from the known plasma concentration :

The glucose metabolization in compartment is proportional to the glucose transport from to . Of course, the glucose metabolites may be transported back to the blood, but we don’t care. We are only interested in glucose. Since it ceases to exist after transport to compartment we ignore all further steps in the metabolic pathway. In our compartment model, it is as if glucose is accumulated in the metabolites compartment. This virtual accumulation rate is the metabolization rate we want to find:

So if we can find the values of the rate constants, we can compute the glucose metabolization rate. As mentioned before, we cannot compute them via the tracer, since it has different rate constants. However, it can be shown that, due to its similarity, the trapping of FDG is proportional to the glucose metabolic rate. The constant of proportionality depends on the tissue type (difference in affinity for both molecules), but not on the tracer concentration. The constant of proportionality is usually called “the lumped constant”, because careful theoretical analysis shows that it is a combination of several constants. So the lumped constant LC is:

For the (human) brain (which gets almost all its energy from glucose) and for some other organs, several authors have attempted to measure the lumped constant. The values obtained for brain are around 0.8. This means that the human brain has a slight preference for glucose: if the glucose and FDG concentrations in the blood would be identical, the brain would accumulate only 8 FDG molecules for every 10 glucose molecules. If we had used radioactive glucose instead of deoxyglucose, the tracer and target molecules would have had identical rate constants and the lumped constant would have been 1. But as mentioned before, with glucose as a tracer, the radioactivity would not accumulate in the cells, which would result in poorer PET images.

The tracer¶

Problem statement¶

Because the lumped constant is known, we can compute the glucose metabolization rate from the FDG trapping rate. To compute the trapping rate, we must know the FDG rate constants. Since the tracer is not in steady state, the equations will be a bit more difficult than for the target molecule. We can easily derive differential equations for the concentration changes in the second and third compartment:

For a cardiac study, we can derive the tracer concentration in the blood from the pixel values in the center of the left ventricle or atrium. If the heart is not in the field of view, we can still determine by measuring the tracer concentrations in blood samples withdrawn at regular time intervals. As with the SUV computations, this requires cross-calibration of the plasma counter to the PET camera.

The compartments and can only be separated with subcellular resolution, so the PET always measures the sum of both amounts, which we will call :

Consequently, we must combine the equations (8) and (9) in order to write as a function of and the rate constants. This is the operational function. Since and are known, the only remaining unknown variables will be the rate constants, which are obtained by solving the operational function.

Deriving the operational function¶

To deal with differential equations, the Laplace transform is a valuable tool. Appendix The Laplace transform gives the definition and a short table of the features we need for the problem at hand. The strength of the Laplace transform is that derivatives and integrals with respect to become simple functions of . After transformation, elimination of variables is easy. The result is then back-transformed to the time domain. Laplace transform of (8) and (9) results in

where we have assumed that at time (time of injection) all tracer amounts are zero. From (11) we find as a function of . Inserting in (12) produces as a function of .

The two factors in can be split from the denominator using the equation

Applying this to (14) and rearranging a bit yields:

Applying the inverse Laplace transform is now straightforward (see appendix The Laplace transform) and produces the operational function:

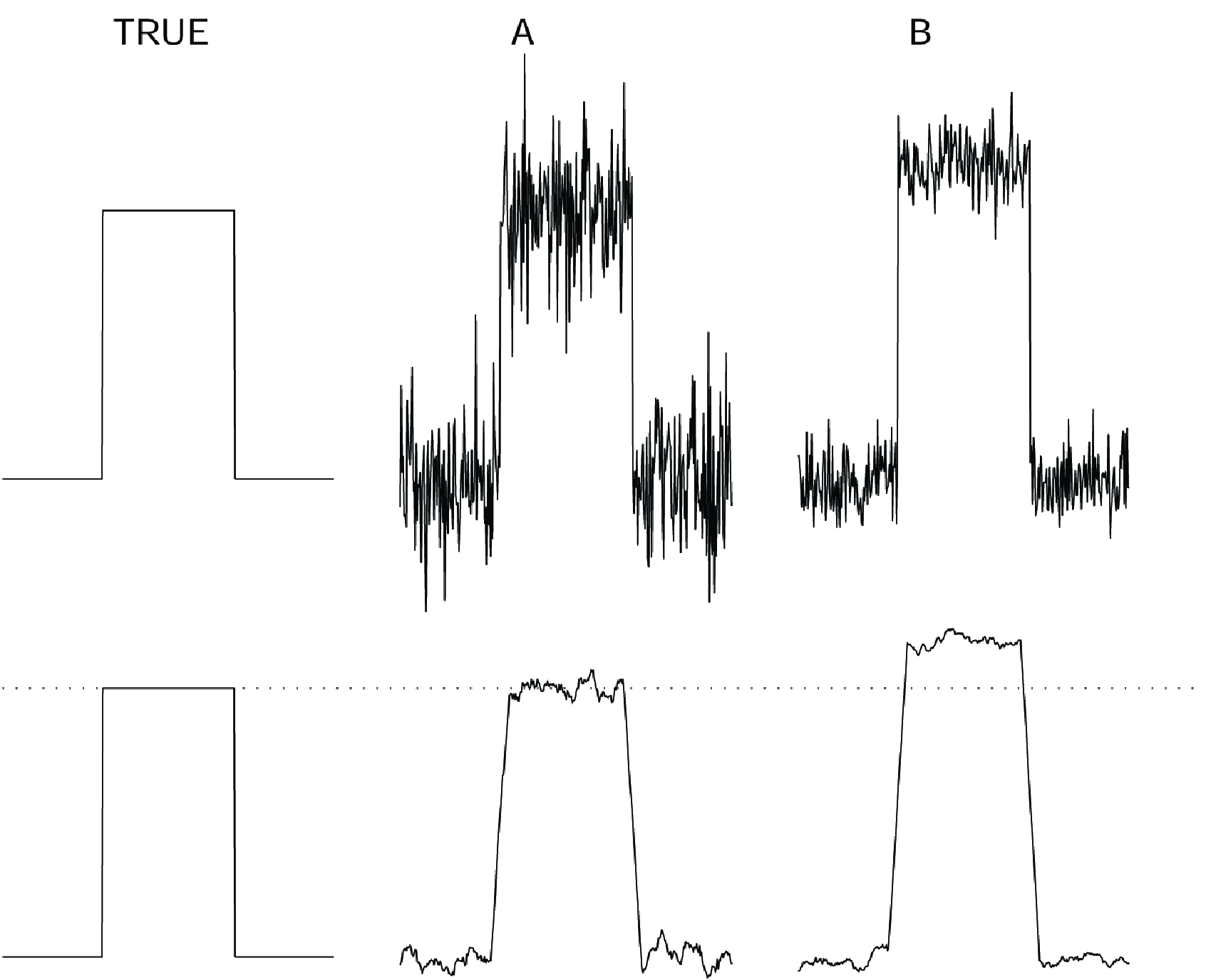

Figure 4:The tracer amount and its two terms when is a step function (equation (17)).

Figure 4 plots and the two terms of equation (17) for the case when is a step function. is never a step function, but the plot provides interesting information. The first term of (17) represents tracer molecules that leave the vascular space, stay a while in compartment and then return back to the blood. As soon as the tracer is present in the blood, this component starts to grow until it reaches a maximum. When becomes zero again, the component gradually decreases towards zero. This first term follows the input, but with some delay (CI1(t) in Figure 4).

The second term of (17) represent tracer molecules that enter compartment and will never leave (CI2(t) in Figure 4). Eventually, they will be trapped in compartment . Note that the first term is not equal to but smaller than . The reason is that part of the molecules in will not return to the blood but end up in . It is easy to compute which fraction of is described by the first term of (17). (The rest of and correspond to the second term of (17)). This is left as an exercise to the reader.

Impulse response¶

Equation (17) can be rewritten as

This is a convolution of the input function with the factor in brackets, showing that that factor is the impulse response function. To illustrate this, we simply compute the response to an impulse, by replacing with a Dirac impulse at time ξ:

Alternative derivation, avoiding the Laplace transform¶

The same result (17) can be obtained with the method of variation of parameters. For simplicity, we set , rewriting equation (8) as follows

First, we solve the corresponding homogeneous equation, obtained by dropping the terms independent of :

The solution is . Now we assume that the solution to (20) is similar, except that the constant must be replaced by a function of : . Inserting this in (20) we obtain:

Having solved the equation for the first tissue compartment, we can use to find the activity in the second compartment. We simply insert (23) in the equation (9) for to obtain:

and therefore

This is the integral of an integral, which may seem somewhat intimidating at first. However, it can be simplified using integration by parts. If you are unfamiliar with that trick, you can easily derive it by noting that the integral of the derivative of the product of two functions and equals:

And therefore we can write

We apply this trick to get rid of the inner integral in (25) as follows:

With these definitions, the left hand side of (27) is equal to (25). Note that here, which makes things slightly simpler. The trick converts (25) into:

where we have replaced β again with . Finally, to obtain we sum (23) and (30):

which is identical to equation (17).

Computing the rate constants with non-linear regression¶

At this point, we have the operational function relating to and the rate constants. We also know and , at least in several sample points (dynamic studies have typically 20 to 40 frames). Every sample point is an equation, so we actually have a few tens of equations and 3 unknowns. Because of noise and the fact that the operational function is only an approximation, there is probably no exact solution. The problem is very similar to the reconstruction problem, which has been solved with the maximum likelihood approach. The same will be done here. If the likelihood is assumed to be Gaussian, maximum likelihood becomes weighted least squares.

With this approach, we start with an arbitrary set of rate constants. It is recommended to start close to the solution if possible, because the likelihood function may have local maxima. Typically the rate constants obtained in healthy volunteers are used as a start. With these rate constants and the known input function , we can compute the expected value of . The computed curve will be diff erent from the measured one. Based on this difference, the non-linear regression algorithm will improve the values of the rate constants, until the sum of weighted squared differences is minimal. It is always useful to plot both the measured and computed curves to verify that the fit has succeeded, since there is small chance that the solution corresponds to an unacceptable local minimum. In that case, the process must be repeated, starting from a different set of rate constant values. The tissue curve in Figure 2 is the result of non-linear regression. The fit was successful, since the curve is close to the measured values.

The glucose consumption can now be computed as

Non-linear regression programs often provide an estimate of the confidence intervals or standard deviations on the fitted parameters. These can be very informative. Depending on the shape of the curves, the noise on the data and the mathematics on the model, the accuracy of the fitted parameters can be very poor. However, the errors on the parameters are correlated such that the accuracy on is better than the accuracy on the individual rate constants.

Computing the trapping rate with linear regression¶

By introducing a small approximation, the computation of the glucose consumption can be simplified. Figure 2 shows a typical blood function. The last part of the curve is always very smooth. As a result, the first term of (17) nicely follows the shape of . Stated otherwise, changes very little over the range where is significantly different from zero. Thus, we can put in front of the integral sign. Since is large relative to the decay time of the exponential, we can set to ∞:

The operational function then becomes:

Now both sides are divided by :

Equation (35) says that is a linear function of , at least for large values of . We can ignore the constants, all we need is the slope of the straight curve. This can be obtained with simple linear regression. For linear regression no iterations are required, there is a closed form expression, so this solution is orders of magnitudes faster to compute than the previous one.

The integral has the unit of time. If would be a constant, the integral simply equals . It can be regarded as a correction, required because is not constant but slowly varying. As shown in Figure 4, when is constant, has a linear and a constant term. Equation (17) confirms that the slope of the linear term is indeed . A potential disadvantage is that the values of the rate constants are not computed.

Image quality¶

It is extremely difficult to give a useful definition of image quality. As a result, it is even more difficult to measure it. Consequently, often debatable measures of image quality are being used. This is probably unavoidable, but it is good to be fully aware about the limitations.

Subjective evaluation¶

A very bad but very popular way to assess the performance of some new method is to display the image produced by the new method together with the image produced in the classical way, and see if the new image is “better”. In many cases, you cannot see if it is better. You can see that you like it better for some reason, but that does not guarantee that it will lead to an improvement in the process (e.g. making a diagnosis) to which the image is supposed to contribute.

As an example, a study has been carried out to determine the effect of 2D versus 3D PET imaging on the diagnosis of a particular disease, and for a particular PET system. In addition, the physicians were asked to tell what images they preferred. The physicians preferred the 3D images because they look nicer, but their diagnosis was statistically significantly better on the 2D images (because scatter contribution was lower).

It is not forbidden to look at an image (in fact, it is usually a good idea to look at it carefully), but it is important not to jump to a conclusion.

Task dependent evaluation¶

The best way to find out if an image is good, is to use it as planned and check if the results are good. Consequently, if a new image generation or processing technique is introduced, it has to be compared very carefully to the classical method on a number of clinical cases. Evaluation must be done blindly: if the observer remembers the image from the first method when scoring the image from the second method, the score is no longer objective. If possible the observer should not even be aware of the method, in order to exclude the influence of possible prejudice about the methods.

Continuous and digital¶

Intuitively, the best image is the one closest to the truth. But in emission tomography, the truth is a continuous tracer distribution, while the image is digital. It is not always straightforward to define how a portion of a continuous curve can be best approximated as a single value. The problem becomes particularly difficult if the images to be compared use a different sampling grid (shifted points or different sampling density). So if possible, make sure that the sampling is identical.

Bias and variance¶

Assume that we have a reference image e.g. in a simulation experiment. In this case, we know the true image, and in most cases it is even digital. Then we can compare the difference between the true image and the image to be evaluated. A popular approach is to compute the mean squared difference:

where and are the image and the reference image respectively. This approach has two problems. First, it assumes that all pixels are equally important, which is almost never true. Second, it combines systematic (bias) and random (variance) deviations. It is better to separate the two, because they behave very differently. This is illustrated in Figure 5. Suppose that a block wave was measured with two different methods A and B, producing the noisy curves shown at the top row. Measurement A is noisier, and its sum of squared differences with the true wave is twice as large as that of measurement B. If we know that we are measuring a block wave, we know that a bit of smoothing is probably useful. The bottom row shows the result of smoothing. Now measurement A is clearly superior. The reason is that the error in the measurement contains both bias and variance. Smoothing reduces the variance, but increases the bias. In this example the true wave is smooth, so variance is strongly reduced by smoothing, while the bias only increases near the edges of the wave. If we keep on smoothing, the entire wave will converge to its mean value; then there is no variance but huge bias. Bias and variance of a sample (pixel) can be defined as follows:

where is the expectation of . Variance can be directly computed from repeated independent measurements. If the true data happen to be smooth and if the measurement has good resolution, neighboring samples can be regarded as independent measurements. Bias can only be computed if the true value is known.

In many cases, there is the possibility to trade in variance for bias by smoothing or imposing some constraints. Consequently, if images are compared, bias and variance must be separated. If an image has better bias for the same variance, it is probably a “better” image. If an image has larger bias and lower variance when compared to another image, the comparison is meaningless.

Figure 5:Top: a simulated true block wave and two measurements A and B with different noise distributions. Bottom: the true block wave and the same measurements, smoothed with a simple rectangular smoothing kernel.

Evaluating a new algorithm¶

A good way to evaluate a new image processing algorithm (e.g. an algorithm for image reconstruction, for image segmentation, for registration of images from different modalities) is to apply the following sequence:

evaluation on computed, simulated data

evaluation on phantom data

(evaluation on animal experiments)

evaluation on patient data

This sequence is in order of increasing complexity and decreasing controllability. Tests on patient data are required to show that the method can be used. However, if such a test fails it is usually very difficult to find out why. To find the problem, simple and controllable data are required. Moreover, since the true solution is often not known in the case of patient data, it is possible that failure of the method remains undetected. Consequently, there is no gain in trying to skip one or a few stages, and with a bit of bad luck it can have serious consequences.

Evaluation on simulation has the following important advantages:

The truth is known, comparing the result to the true answer is simple. This approach is also very useful for finding bugs in the algorithm or its implementation.

Data can be generated in large numbers, sampling a predefined distribution. This enables direct quantitative analysis of bias and variance.

Complexity can be gradually increased by making the simulations more realistic, to analyze the response to various physical phenomena (noise, attenuation, scatter, patient motion …).

A nice thing about emission tomography is that it is relatively easy to make realistic simulations. In addition, many research groups are willing to share simulation code.

It is possible to produce simulations which are sufficiently realistic to have them diagnosed by the nuclear medicine physicians. Since the correct diagnosis is known, this allows evaluation of the effect of the new method on the final diagnosis.

When the method survives complex simulations it is time to do phantom experiments. Phantom experiments are useful because the true system is always different from even a very realistic simulation. If the simulation phase has been done carefully, phantom experiments are not likely to cause much trouble.

A possible intermediate stage is the use of animal experiments, which can be required for the evaluation of very delicate image processing techniques (e.g. preparing stereotactic operations). Since the animal can be sacrificed, it is possible, at least to some extent, to figure out what result the method should have produced.

The final stage is the evaluation on patient data, and comparing the output of the new method to that of the classical method. As mentioned before, not all failures will be detected since the correct answer may not be known.

- SR Cherry, JA Sorenson, & ME Phelps. (2012). Physics in Nuclear Medicine. Saunders. 10.1016/B978-1-4160-5198-5.00001-0