In nuclear medicine, photon energy ranges roughly from 60 to 600 keV. For example, 99mTc has an energy of 140 keV. This corresponds to a wave length of 9 pm and a frequency of 3.4 Hz.

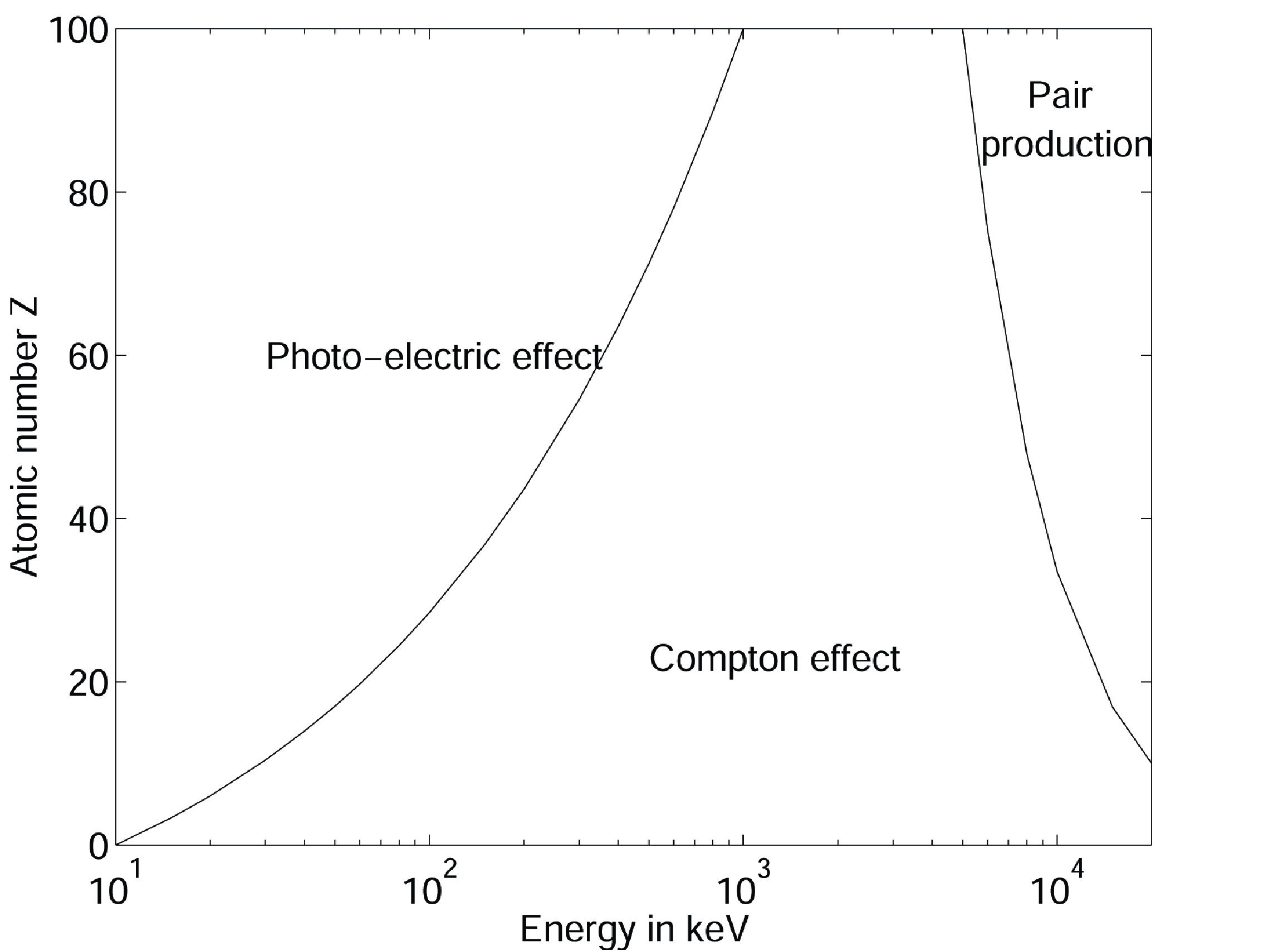

At these energies, the dominating interactions of photons with matter are photon-electron interactions: Compton scatter and photo-electric effect. As shown in Figure 1, the dominating interaction is a function of energy and electron number. For typical nuclear medicine energies, Compton scatter dominates in light materials (such as water and human tissue), and photo-electric effect dominates in high density materials. Pair production (conversion of a photon in an electron and a positron) is excluded for energies below 1022 keV, since each of the particles has a mass of 511 keV. Rayleigh scatter (absorption and re-emission of (all or a fraction of) the absorbed energy as a photon in a different direction) has a low probability and its effect can be ignored in PET and SPECT imaging.

Figure 1:Dominating interaction as a function of electron number Z and photon energy.

Photo-electric effect¶

A photon “hits” an electron, usually from an inner shell (strong binding energy). The electron absorbs all the energy of the photon. If that energy is higher than the binding energy of the electron, the electron escapes from its atom. Its kinetic energy is the difference between the absorbed energy and the binding energy. In a dense material, this photo-electron will collide with electrons from other atoms, and will lose energy in each collision, until no kinetic energy is left.

As a result, there is now a electron vacancy in the atom, which may be filled by an electron from a higher energy state. The difference in binding energy of the two states must be released. This can be done by emitting a photon. Alternatively, the energy can be used by another electron with low binding energy to escape from the atom.

In both cases, the photon is completely eliminated.

The probability of a photo-electric interaction is approximately proportional to , where is the atomic number of the material, and is the energy of the photon. So the photo-electric effect is particularly important for low energy radiation and for dense materials.

Compton scatter¶

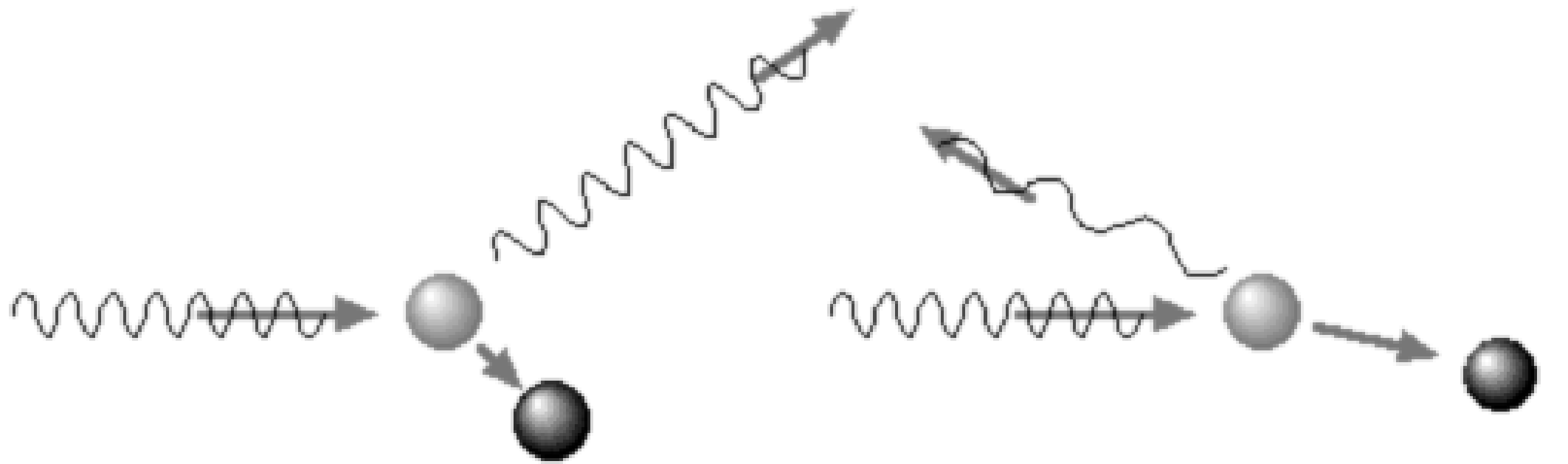

Figure 2:Compton scatter can be regarded as an elastic collision between a photon and an electron.

Compton scatter can be regarded as an elastic collision between a photon and an electron. This occurs with loosely bound electrons (outer shell), which have a binding energy that is negligible compared to the energy of the incident photon. The term “elastic” means that total kinetic energy before and after collision is the same. As in any collision, the momentum is preserved as well. Applying equations for the conservation of momentum and energy (with relativistic corrections) results in the following relation between the photon energy before and after the collision:

with

The expression is the energy available in the mass of the electron, which equals 511 keV. For a scatter angle θ = 0, the photon loses no energy and it is not deviated from its original direction: nothing happened. The loss of energy increases with θ and is maximum for an angle of 180º. The probability that a photon will interact at all with an electron depends on the energy of the photon. If the interaction takes place, each scatter angle has its own probability, and this probability is proportional to the differential cross section, given by the Klein-Nishina equation:

where is the classical electron radius and is defined above. The cross section σ has the unit of area, Ω is the solid angle. Integrating over Ω would produce the total cross section for Compton scatter. For that integration, can be written as [1]

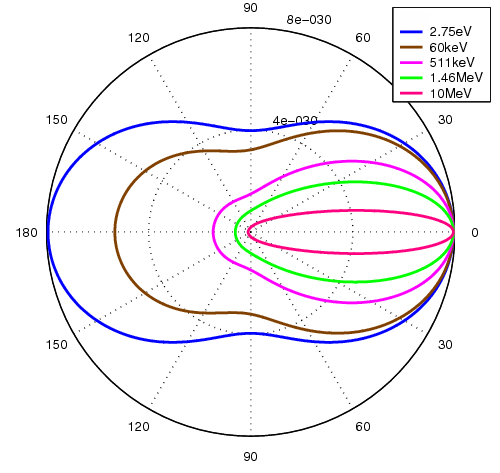

The differential cross section (3) is shown for a few incoming photon energies in Figure 3. For higher energies, smaller scatter angles become increasingly likely.

Figure 3:The scattering-angle distribution for a few photon energies. Figure from Wikipedia (Klein-Nishina formula).

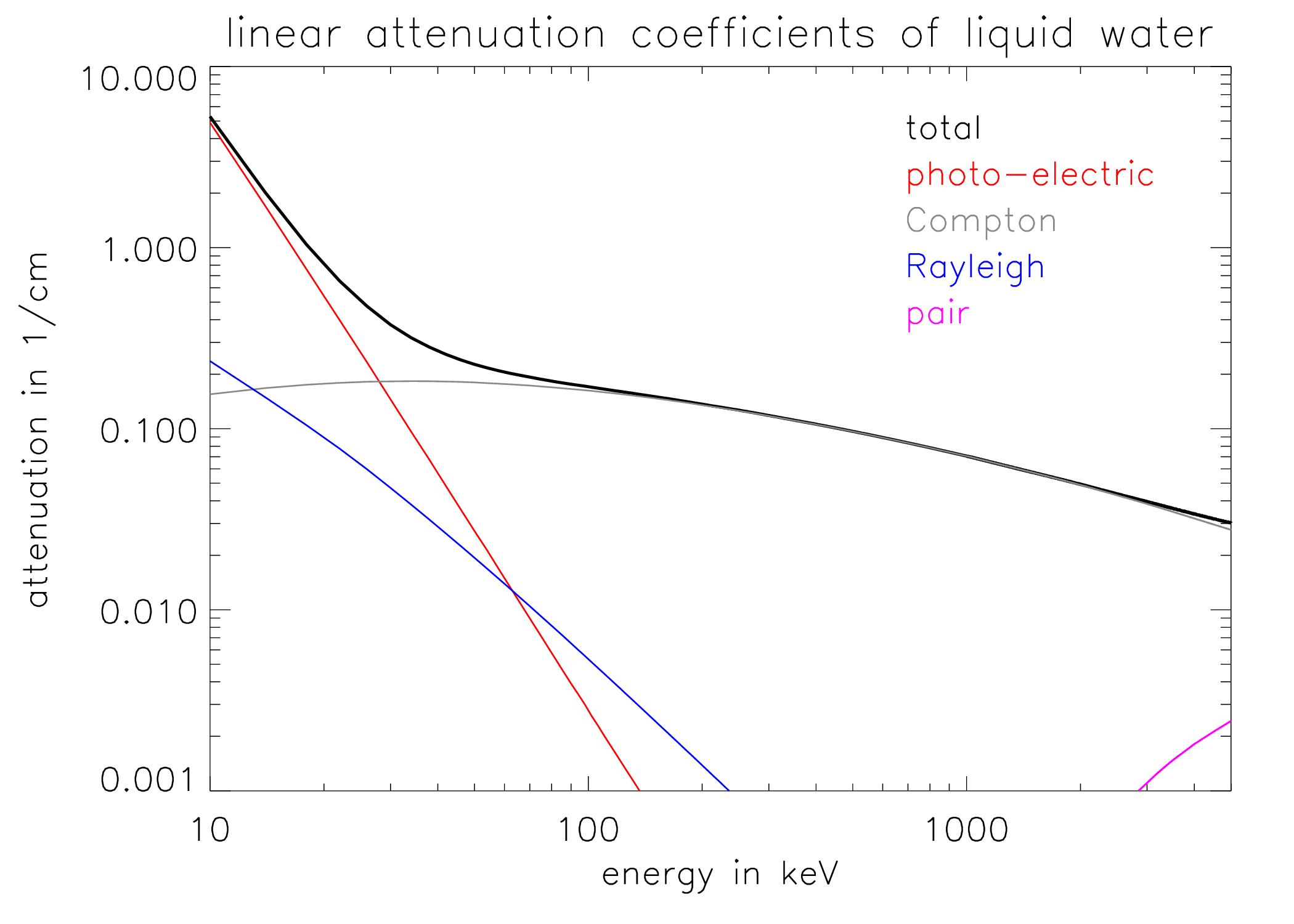

The probability of a Compton decreases very slowly with increasing (see Figure 4) and with increasing .

Because the energy of the photon after scattering is less than before, Compton scatter is sometimes also called “inelastic scattering”.

Attenuation¶

Figure 4:Photon attenuation in water as a function of photon energy. The photo-electric component decreases approximately with (of course, is a constant here). The Compton components varies slowly.

The linear attenuation coefficient μ is defined as the probability of interaction per unit length (unit: cm-1). Figure 4 shows the mass attenuation coefficients as a function of energy in water. Multiply the mass attenuation coefficient with the mass density to obtain the linear attenuation coefficient. When photons are traveling in a particular direction through matter, their number will gradually decrease, since some of them will interact with an electron and get absorbed (photo-electric effect) or deviated (Compton scatter) into another direction. By definition, the fraction that is eliminated over distance equals :

If initially photons are emitted in point along the -axis, the number of photons we expect to arrive in the detector at position is obtained by integrating (4):

Obviously, the attenuation of a photon depends on where it has been emitted.

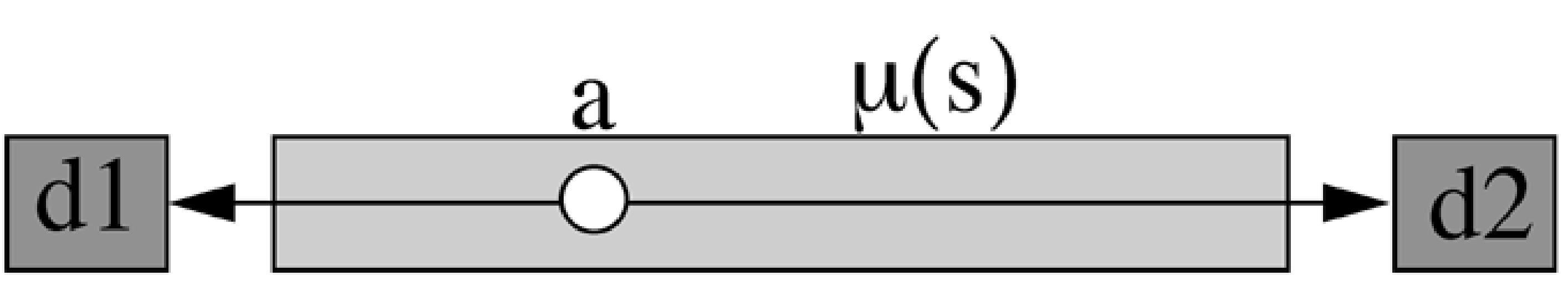

Figure 5:Positron emitting point source in a non-uniform attenuator.

For positron emission, a pair of photons need to be detected. Since the fate of both photons is independent, the detection probabilities must be multiplied. Assume that one detector is positioned in , the second one in , and a point source in , somewhere between the two detectors. Assume further that during a measurement, photon pairs were emitted along the -axis (Figure 5). The number of detected pairs then is:

Equation (7) shows that for PET, the effect of attenuation is independent of the position along the line of detection.

Photon-electron interactions will be more likely if there are more electrons per unit length. So dense materials (with lots of electrons per atom) have a high linear attenuation coefficient.